How much does the State spend on housing? Well, unsurprisingly, it depends on how you count it.

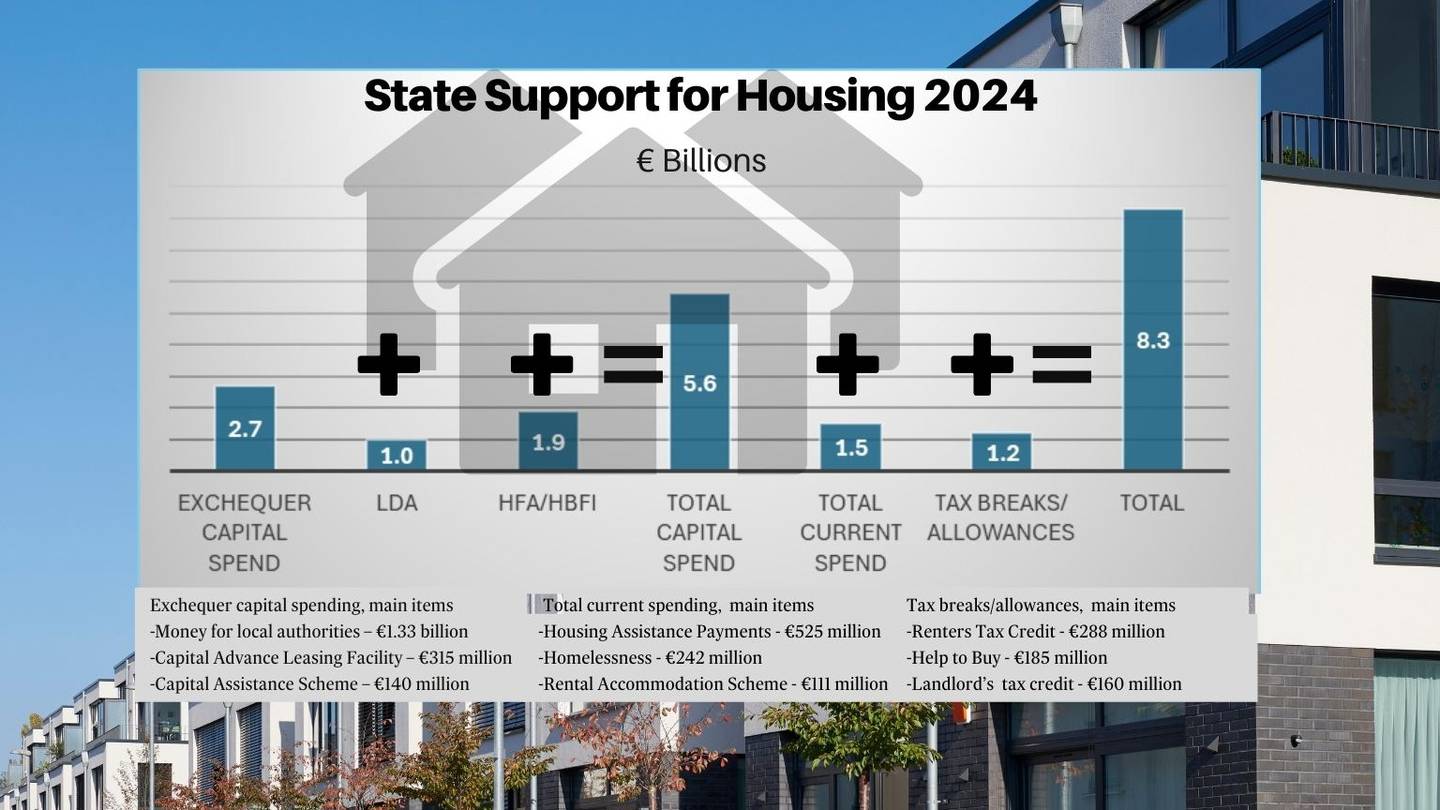

However, a few key points are clear. The first is that the total is very significant. Our calculation of gross spending and tax breaks (spending by another name) this year adds up to €8.3 billion. In the context of an annual State budget of €100 billion or so, this is a big chunk.

The second is that the amount spent has risen very significantly in recent years. Measured from the trough of State spending in 2014, total supports have grown to 3½ times what they were a decade ago. Spending after the financial crash was, of course, at a historic low, but by any standards the rise in recent years has been rapid.

The third point is that the figure is set to grow further. The chronic shortage of social homes remains to be addressed – it is a result of low levels of construction of new social homes for close to a decade, combined with the tenant purchase schemes run by local authorities, which allow long-term council tenants to buy the properties at a significant discount. As a result, councils were unable to replenish their social housing stock.

Consequently, a total of 58,824 households were identified as having unmet social housing needs at the end of last year, with this figure excluding those in receipt of private rental support schemes – meaning the actual demand for secure social homes is much higher. With homeless numbers regularly hitting new records, and social housing need increasing, expenditure in this area is expected to escalate.

Pressure is also on to increase the supply of housing generally – particularly when it comes to affordable homes. Many of the State investment supports have only started in recent years and are likely to ramp up further. If Sinn Féin gets into government after the next general election, the mix may be different – it has promised to end support for buyers and to increase spending on the provision of social and affordable homes. But whoever is in power, the State commitment to housing looks to be only going one way: higher.

State resources for housing fall into three main areas. The first is capital or investment spending – building or buying houses or helping to fund others to do so. The second is current or day-to-day spending, the huge array of State supports which help people to access housing. And the third is a variety of tax breaks and allowances designed both to help buyers and offer incentives to those building homes.

1. Capital spending

The total State, or State-backed investment in housing this year is well in excess of €5 billion.

State investment has increased swiftly in recent years as political pressure has grown to build more homes. This has included spending directly by the State, by local authorities and by approved housing bodies and includes cash advanced by the Land Development Agency (LDA), the Housing Finance Agency (HFA) and Home Building Finance Ireland (HBFI).

As the HFA is by way of loan support to local authorities, housing bodies and universities to build student accommodation – and will thus in time be repaid – it is somewhat different from direct State spending. So is the funding loaned to the private sector by the HBFI. But as both organisations are underwritten one way or the other by the State, it seems legitimate to include them.

State investment

Direct State capital investment in housing this year in the Department of Housing budget is €2.7 billion. The bulk of this – €1.86 billion – goes to local authorities and approved housing bodies via a series of schemes which support building, help to get access to borrowing from elsewhere – including the HFA – or fund the leasing of properties or purchase of properties for social housing.

In the chain of supports, the Government funds local authorities to purchase properties, finance direct builds, regeneration and other projects, and also for them to provide loans to approved housing bodies (AHBs) – independent not-for-profit bodies which provide affordable housing – for them to construct or purchase homes. AHBs can also borrow from local authorities or the HFA directly. In turn HFA borrowing is underwritten by the State.

The State, in other words, is deeply entwined in the whole process at every step.

New schemes

An additional suite of supports – surrounded by a sea of acronyms – have been introduced in recent years, largely to support private builders and AHBs in bringing forward and completing schemes. In effect, the State is underwriting or part-underwriting these developments, reducing the risk for developers. These include initiatives such as the Croí Cónaithe fund, which provides finance for building apartments for sale to owner occupiers and also to refurbish vacant properties. A new secure tenancy affordable rental (Star) scheme provides equity to private developers and AHBs to build cost-rental homes, along with a cost rental equity loan (Crel) scheme which loans money to approved housing bodies for these developments. Many of these schemes have been tweaked and changed and the cost can be expected to rise further.

State agencies

In addition to these direct State investments, the 2024 housing spending plans include just under €1 billion being deployed by the LDA, which builds on State land and more recently partners with private developers to try to get developments finished out. This latter extension of its mandate is significant, as the State tries to step in to allow projects to overcome what was seen as a viability gap which risked stalling many developments.

A total of €1.5 billion is expected to be advanced by the HFA. It raises borrowings on the market but, as these are guaranteed by the State and it advances loans on a favourable basis, it needs to be counted as State-supported spending.

The final sum included in the calculation of capital spending is money advanced by HBFI, established in 2019 to seek to improve the flow of finance to private developers and funded initially by €730 million from the Ireland Strategic Investment Fund. Its loan portfolio at the end of last year was more than €1.6 billion – and had grown by €400 million last year. A similar allowance is made in our figures for 2024. While the HBFI operates on a fully commercial basis, its State funding and ownership indicates that it is an important part of Government policy to fund the sector.

2. Current spending

Social Housing

A total of €1.5 billion is set aside in this year’s Department of Housing budget for current expenditure. Social housing, which is housing provided for those on low incomes, makes up a large proportion of this. And it continues to rise, having more than quadrupled over the past decade.

One element behind the surge in spending is the sale of local authority homes to long-term tenants. A 2018 report by UCD academic Prof Michelle Norris found two-thirds of the total council dwellings provided have been sold to tenants at a discounted rate.

Ireland operates on a boom-bust cycle for construction of homes, meaning that for many years governments were not building social housing units. Combine this with the fact that they were selling their existing stock, and it has resulted in skyrocketing demand for a too-small, albeit growing, supply.

Construction of these homes is back up and running, though the delivery of new units is not yet at the pace required to meet the population’s needs. As a result, the Government has had to find alternative ways to provide homes to those with social housing needs. The two main ways through which this is done are the Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) and the Rental Accommodation Scheme (RAS). This year, €525 million is set aside for HAP, and €111 million is set aside for RAS, which are paid directly to private landlords so tenants on the social housing list pay less than market rents.

A further €62.7 million was allocated for rent supplement, a short-term income support for people in the private rented sector.

For social housing tenants in local authority accommodation, differential rents are used, which are considerably lower than market rates and are directly linked to tenants’ incomes. Though there is no upfront cost to the exchequer for this rent reduction, there is still a subsidy.

A 2015 report published in the Economic and Social Review estimated differential rents cost in the region of €575 million that year. For our calculations, we have not included this subsidy in our total figure; economists and housing experts have said it would be difficult to quantify it due to the significant variation in how the system is applied across the local authorities, as well as how much the rental sector has changed since then.

The Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) in 2022, for example, found the rent paid by a lone parent with two children earning €25,000 per year ranges from between €226 and €450 per month, depending on tenant location.

One thing that makes Ireland markedly different from its European counterparts in this regard is the fact that other countries tend to set rents for local authority tenants at a cost-recovery level. Given that’s not the system under which we have operated – though a cost-rental model is now being rolled out – the Government must annually allocate funding for the maintenance and refurbishment of these properties, with €31 million set aside this year for a scheme for this.

As this cost-rental model grows in Ireland – offering rents below full market levels but enough to recoup the costs of building and maintaining the scheme -the calculation of the underlying level of State support will be complicated here, too.

The mortgage-to-rent (MTR) scheme is another social housing initiative. Under this, a homeowner who ends up in mortgage arrears sells the home to a provider of the MTR scheme, and the individual can continue to live there as a social housing tenant. A total of €18 million has been allocated for the programme this year.

Homelessness

There is, of course, also the spending on homelessness. As the number of people in emergency accommodation has increased, so too has the amount spent accommodating these individuals. This year, a total of €242 million has been set aside for homelessness services.

According to a 2021 report from the Department of Housing, there had been a 26 per cent annual average increase in spending on homelessness since 2014 – when the department first began to publish figures on the number of people in emergency accommodation. However, the report highlighted the €270.9 million in 2020 was higher than average due to carry-over of spending from the previous year.

Further to this, there is an acquisition fund of €35 million this year for Housing First. Under this, individuals with complex needs who are long-term homeless are provided with a home without any conditions of sobriety or treatment, and are then provided with wraparound services.

Other schemes

Outside of the big headline expenditure, there are other schemes that are less well flagged, though which still make up a hefty sum. There is the allocation of €28 million for Traveller-specific accommodation, €90 million for energy retrofitting, €70 million for construction defects and €3.3 million for housing for people with a disability or older people.

For a housing system to function effectively and fairly, there is also a need for public money to be set aside for regulation. This was done through a variety of different measures in Budget 2024.

More than €13.5 million was set aside for the Residential Tenancies Board (RTB), €9 million has been allocated for rented accommodation inspections, some €17.5 million for the housing and sustainable communities agency and more than €3.35 million was being set aside for the AHB regulatory authority.

3. Tax breaks and reliefs

The usual focus is on money spent by the exchequer. But special tax reliefs also cost the exchequer due to revenue foregone – and are important policy interventions which can have a significant impact on the housing market. In the past, large property reliefs were one of the reasons why the property market overheated: as well as encouraging useful developments, they led to many of the wrong types of property being built in areas where there was no demand. They also often acted as tax shelters for better-off people, cutting their tax bills as part of schemes drawn up by tax advisers.

Since the financial crash, governments have been cautious about tax breaks. But they are still a key factor in the market. On the buyer side, the key incentive is the Help-to-Buy scheme, which is a tax refund of income tax and deposit interest retention tax paid by first-time buyers. Its estimated cost for this year is a hefty €185 million. First-time buyers can also get support under the First Home Scheme, counted as part of the Department of Housing budget. Buyers who cannot get access to commercial loans can also get finance via a loan scheme run by local authorities.

Another measure to be noted is the recent extension of the waiver on development levies and connection charges paid by developers of new homes (not technically taxes – but this also operates like a tax relief). The annual cost of the extension is €240 million.

A number of important newer reliefs relate to the rental market. The renters’ tax relief was extended as part of this year’s budget and now has an estimated annual cost of €288 million. The new landlords’ credit, meanwhile, has an estimated cost this year of €45 million but this will rise to €160 million by 2026. A one-year mortgage interest relief scheme will cost some €125 million.

Costing the element of tax breaks which could qualify as special incentives is not always straightforward. Take the general tax treatment of landlords – this involves elements such as the write-off of mortgage relief and incentives to try to encourage refurbishment of older properties which could be considered generous, but also general write-offs for improvements and repairs, which is more in the normal course of business.

A total of €1.2 billion was claimed by private landlords in 2022 (the most recent figures available). The cost of this depends on the rate at which the landlords pay tax – taking a middle figure of 30 per cent leaves an annual cost of these reliefs of around €400 million, which we have also included in our totals.

Separately, the rent a-room tax relief – aimed at non-landlords who have a room to spare – is estimated to have cost €27.9 million in 2020. This has probably increased subsequently given the upward trend in the use of this scheme.

There are other, lower-cost, initiatives, such as the Living City scheme, which aims to encourage inner-city development and has had a limited uptake, and the residential stamp duty relief, which offers a refund where building eventually takes place on land bought for non-residential purposes. This cost €17.6 million in 2020.

More existential questions lurk, too. As well as “tax expenditures”, the State also raised tax revenue from housing. For the purposes of our calculation we are not netting this off. Nor is there any allowance for the fact that people’s principal private residence is exempt from capital gains tax, a relief which the Commission on Taxation and Welfare recommended should slowly be withdrawn, though noting there was no estimate on its considerable cost.

The revenue foregone here would be hugely significant, and the Fiscal Advisory Council has tentatively estimated that a restriction of the relief could raise €400 million in tax – and more could be raised by changing tax relief on inheritances. However, we have not included this in our overall totals.

Where next?

The next key pointer will be the publication of the report of the Commission on Housing, a Government-commissioned document recently submitted to the Department of Housing. The commission was charged with looking at the mix of supports and State regulation of the sector and advising on where to go next.

A key issue will be its assessment of the value for money and efficiency of the money which is currently being spent – as well as recommendations on what to do next. In turn this will set the ground for the general election debate to come.

With vast State resources in play and huge political pressure to make progress, there is a lot at stake.